What does the 20th century look like?

It is, of course, a hopeless question to answer, what a whole century looks like. And it must also be asked, when did the 20th century actually begin and when does it end?

This seems confusing. But if we think about the chronological time measured in years and centuries and at the same time think about the time cultural expressions take to be formed, developed, used and abandoned, these two time courses will not completely overlap. Some of the 20th century artefacts groups started their development series sometime in the 19th century and some still persist. Some series or sequences extend over many decades, others over shorter periods of time. For a museum of both cultural history and art history, this is a question that must be taken seriously when we are to select, present and convey things, whether it is lamps, desks, ornaments, ceramic sculptures, textile patterns, costumes, shoes - or paintings. permanent exhibition of objects that we have called Objects for modern life is about just this. It is a continuation of the exhibitions in Nøstetangenrommet which show exquisite art industry from the 18th century, Glimmer og gavn which shows beautiful objects from bourgeois 19th century homes, and the exhibition Objects for life which shows both the church room's objects and city interiors, and the latter focuses on the colorful bushes. folk art, objects that marked the life of the peasant society for use and for decoration. By going through these cultural-historical exhibitions at Drammens Museum, we see that changing times look different. The forms change and form what the art historian George Kubler called The Shape of Time, the title of an important book that came out in 1962. What is especially important to try and bring out in an exhibition with objects for modern life is that the modern object design, production, turnover and distribution differ quite sharply from the production of objects of earlier times. The beginnings of modern cultural history largely coincide with the greatest change in human life in long, long periods of time. What we like to call the great change of heart, when the agricultural society in the countryside ruled by the cyclical time of the seasons and the connecting role of the extended family, was changed by the development of the industrial society, with the dissolution of old ways of life. A linear, progressive understanding of time followed, where work was measured in time units of working time against a salable production unit, a factor that formed the basis for wage determination and calculated profit. Life was seen as something to develop and make progress, and people moved to the cities to find paid work. The family was replaced with the nuclear family or a life as a single person, and the farm and the homestead were replaced with an apartment and dormitory. The modern detached houses became laboratories where the lifestyle of the new sense of form was tested. Therefore, modern object culture also contains expensive luxury products, in parallel with affordable mass-produced items. This change was both made possible and accelerated by technological advances and an increasingly efficient organization of work. Items that accompanied the families were replaced by goods that were bought, used and thrown away when they broke or went out of fashion. Things were "consumed." Replacing the "salon" and "modernizing" the home are typical phenomena in the 20th century's use and experience of things. After the serious start of industrial mass production of affordable, simple and elegant objects, the phenomenon of replicas and copies also became widespread. At the same time, the history of 20th-century artefacts became an international phenomenon; things could be used everywhere, and ideas and forms were spread all over the western world. The 20th century was marked by a distancing from provincialism and narrow nationalism, and Norway became, after the national romanticism, again part of a larger world of things. There was such a sharp increase in the number of objects designed and produced throughout the 20th century that we are witnessing an exponential increase in the number of items. An increase in the number of items and pressure on production prices could create simple and poorly durable goods, and this makes the selection of representative items demanding. George Kubler distinguishes between primary objects and lines. For example. the artisan style within the Art & Crafts movement will be examples of late editions of a traditional sequence by maintaining a high standard for good, still handmade objects, while the Bauhaus style's series-produced furniture with chrome-plated, curved metal tubes in interaction with textiles, rubber, leather and thin wood panels shows primary objects that started the entire international design movement in its most radical form. The exhibition is therefore built around some design icons, late or early in the sequence, which when experienced in sequence will be able to show a precise and very simplified passage through the 20th century object history.

Objects for modern life opened on Thursday, October 19, 2017.

Åsmund Thorkildsen

Museum director

Josef Hoffmann's armchair from 1899 and Vienna Secession side table from approx. 1905 (Gustav Siegel), and fruit basket in silver from Wiener Werkstätte from 1904 (Koloman Moser).

Jug with lid, candlestick and vase designed by Swedish Inger Persson in the 1960s.

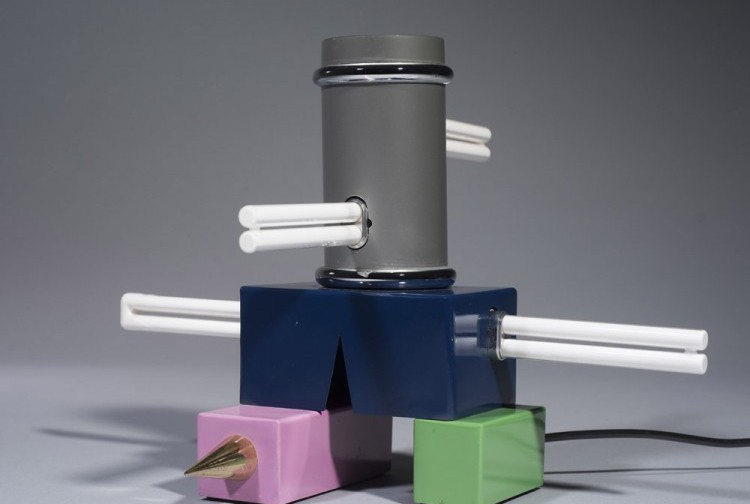

Peter Shire, the lamp Laurel from 1985 designed for Memphis Milano.

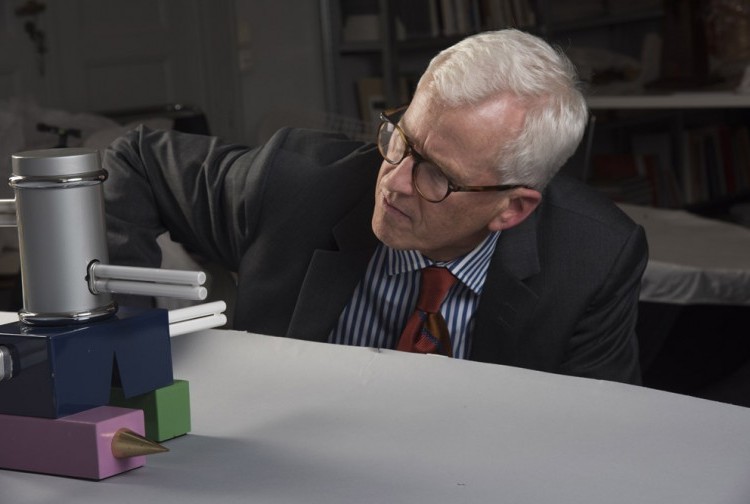

The exhibition is curated by museum director Åsmund Thorkildsen.

See also...

The pleasure garden at Marienlyst

The Marienlyst project – revitalization, anchoring and inclusion

Opening of Perspektiv Drammen - Artwork from the museum's collections

Perspective Drammen

Artwork from the museum's collections

22.02.24-04.08.24

Opening of the November exhibition 2023

22.11. opened Buskerud Visual artists and Drammens Museum November exhibition 2023. We welcome you to a great exhibition in the Lychepaviljon from 23.11.23 to 07.01.24

The November exhibition 2023

The November exhibition 2023 opens on Wednesday 22 November at 18:00